African American music has always been about taking someone there. Wherever it is, it is somewhere other than Jim Crow America, somewhere beyond the confines of the oppressive spaces in the U.S.A. where Blackness is somehow a curse rather than a treasure. So the great recording artists of the 20th century, from Duke Ellington to Charlie Parker to Nina Simone to Aretha Franklin to James Brown, all sought to create a world where one can inhabit the space and not feel the sting of oppression, to relish in that moment and feel one’s freedom. A great many artists from Ohio began celebrating that freedom as soon as they crossed the Mason-Dixon Line on that mid-century Great Migration north.

It’s well known that Dayton’s Black community was stable and sturdy and provided many young players of the era with opportunities to learn music, to purchase instruments, to practice and to develop into bands. With the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base providing employment, and as the home of Project Blue Book — investigating UFO’s in the 1960s — one might say extra-terrestrial inspiration to the Black community, Dayton musicians were not engaged in Black music traditions so much as breaking them.

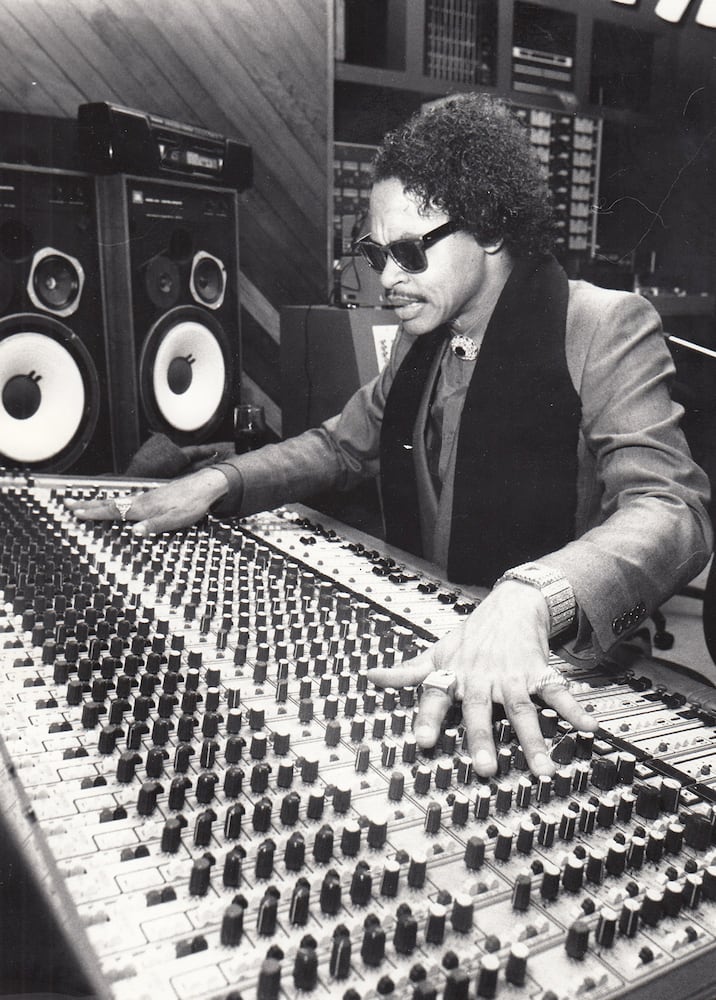

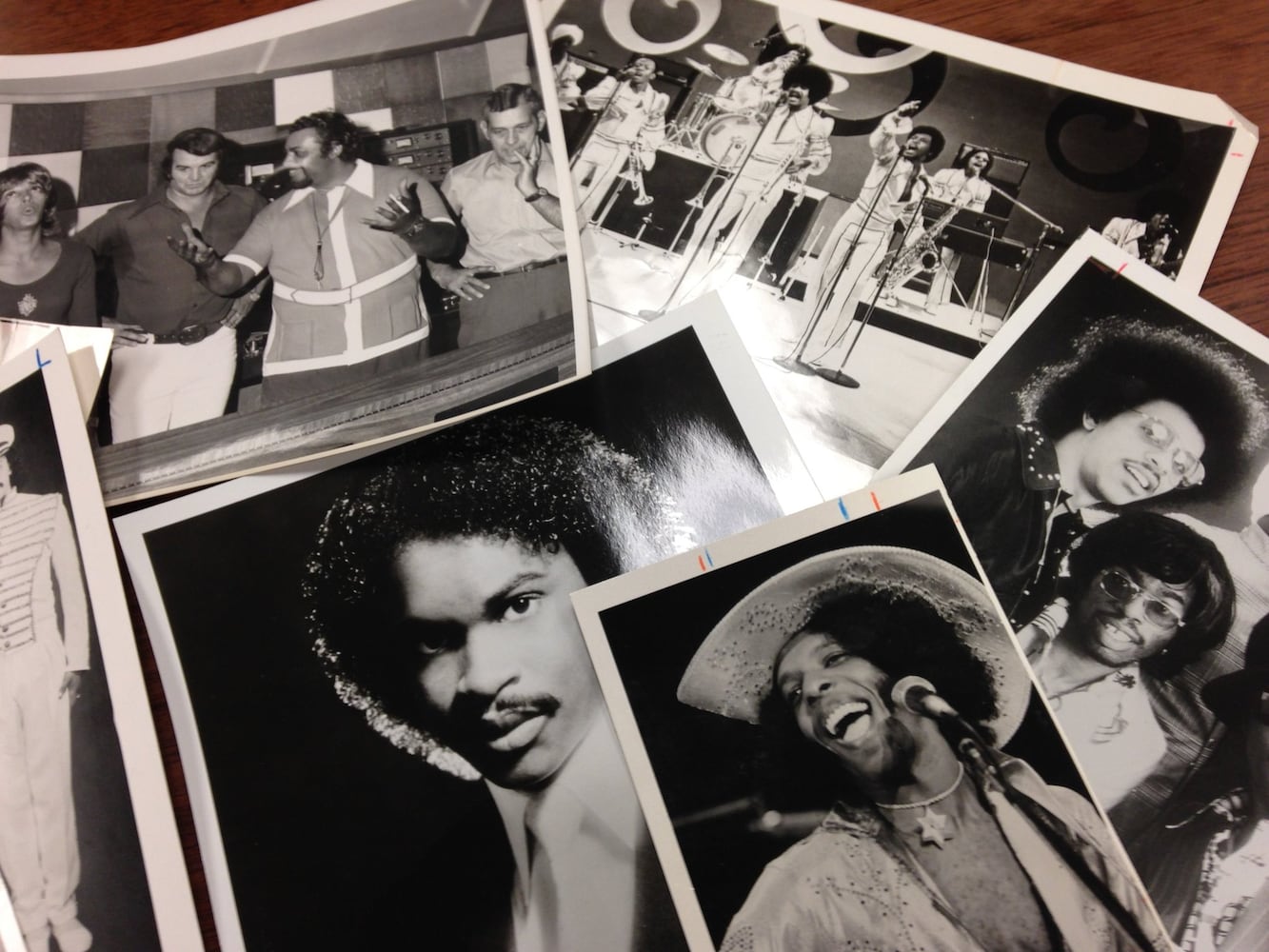

In 1972 Walter “Junie” Morrison of the Ohio Players tinkered with the sounds on his new ARP 1000 synthesizer and contrived the Funky Worm (“that could play guitar without any hands!”), which developed into a #1 R&B hit, and became a staple of hip hop samples for decades.

Ohio Players’ guitarist Leroy “Sugarfoot” Bonner was a bona fide blues giant, but in the Players he pushed the sound beyond traditional boundaries. The swinging feel of “Jive Turkey part 1″ had a familiar down-home blues pace, but the extended version was another matter. The wildly original inverted funk arrangement of “Jive Turkey part II” took the blues down a roller-coaster of a winding road, that let fans of the multi-platinum band know both where their roots were, and where the future was going.

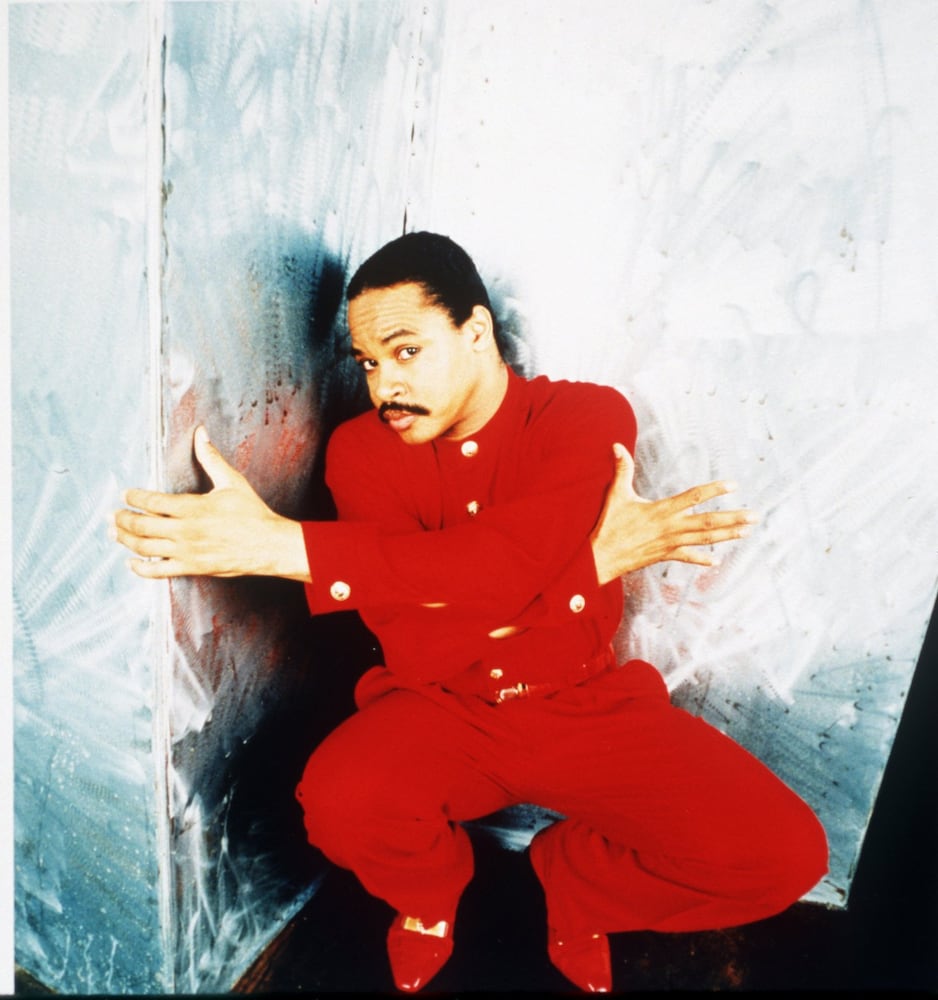

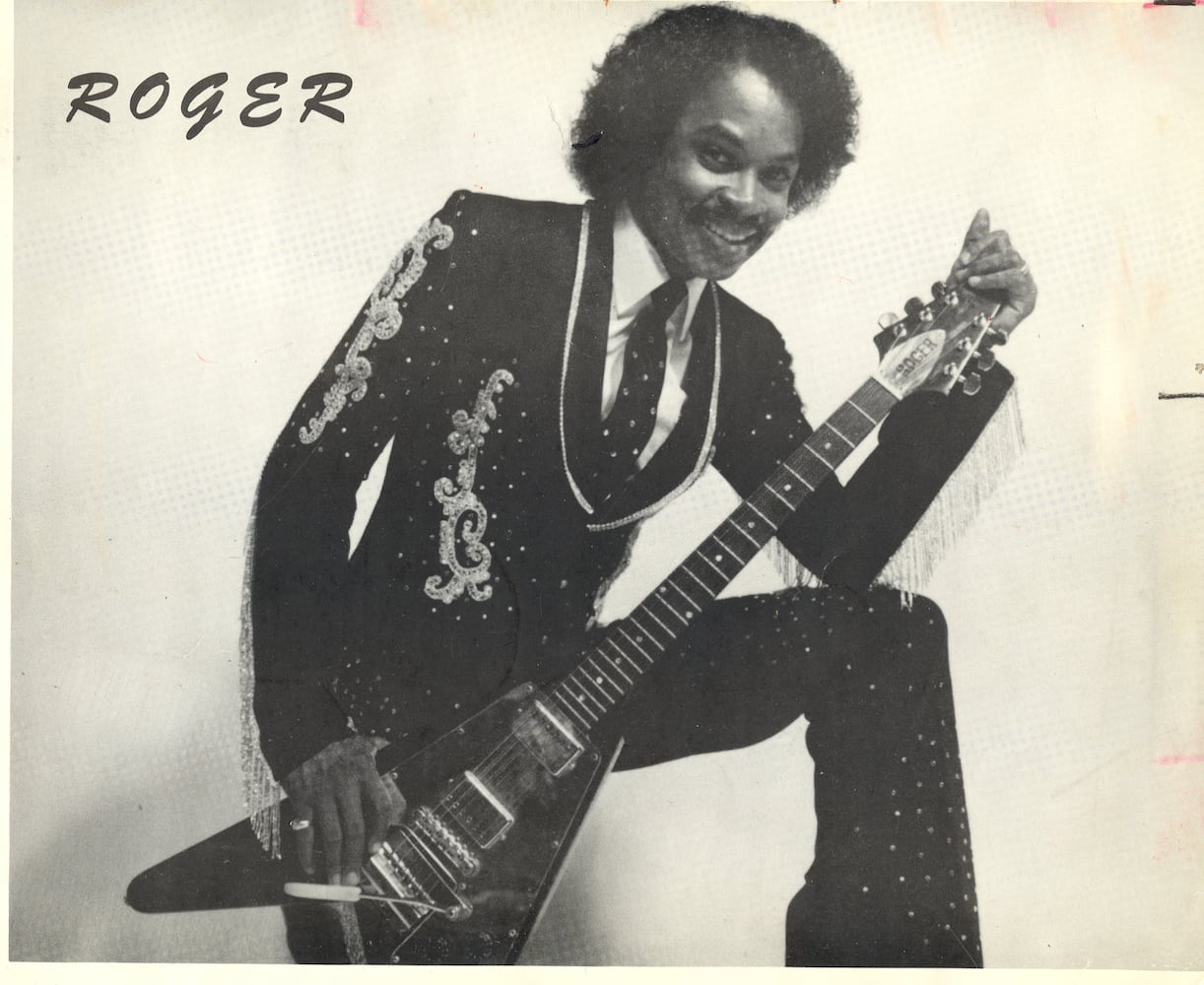

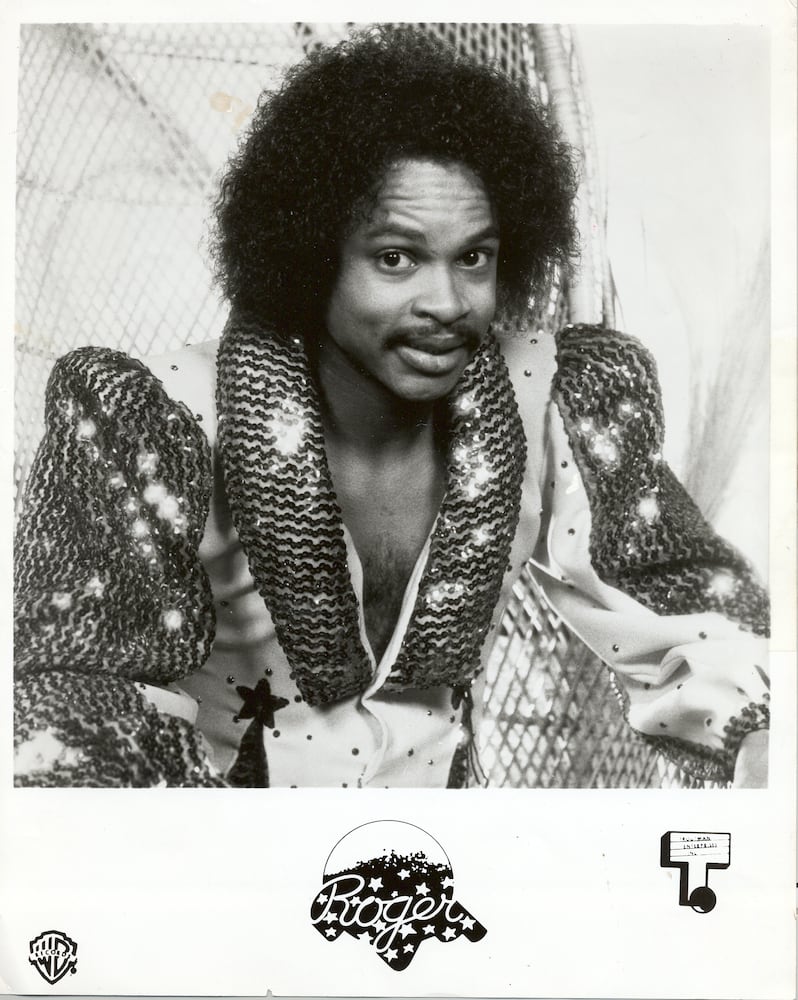

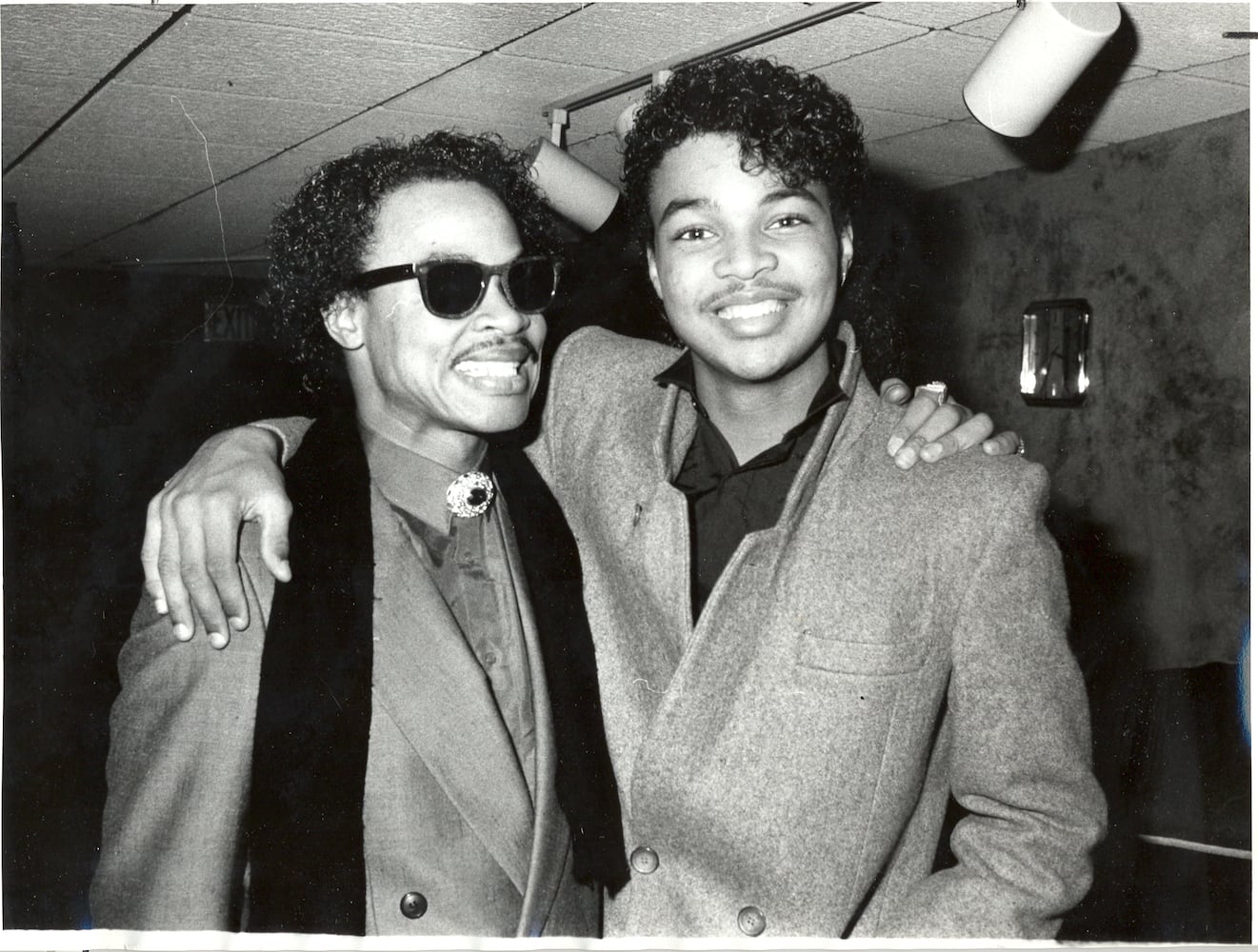

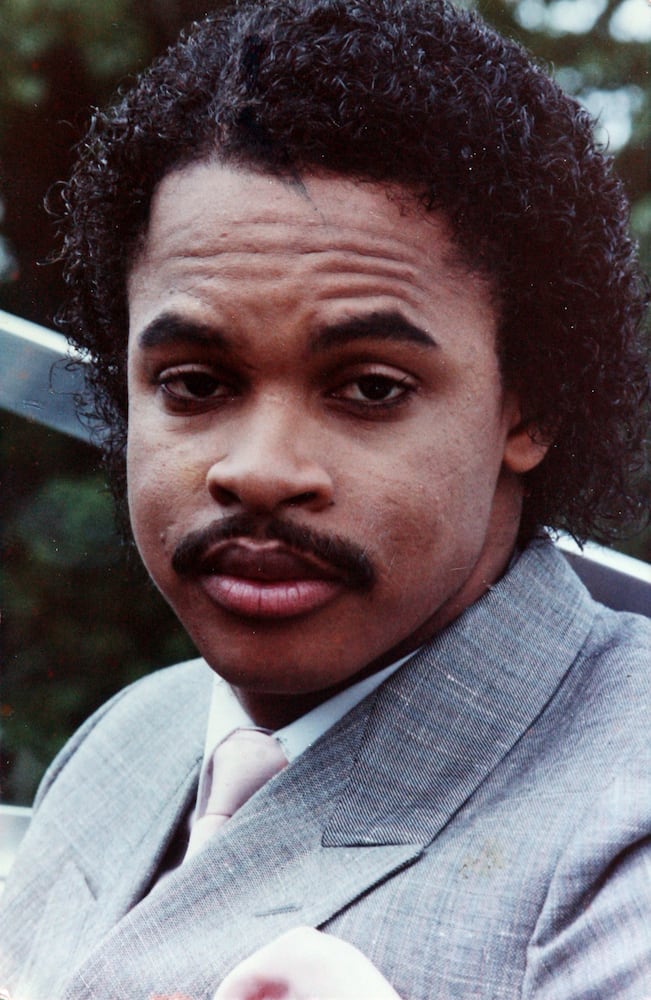

Credit: Contributed photo

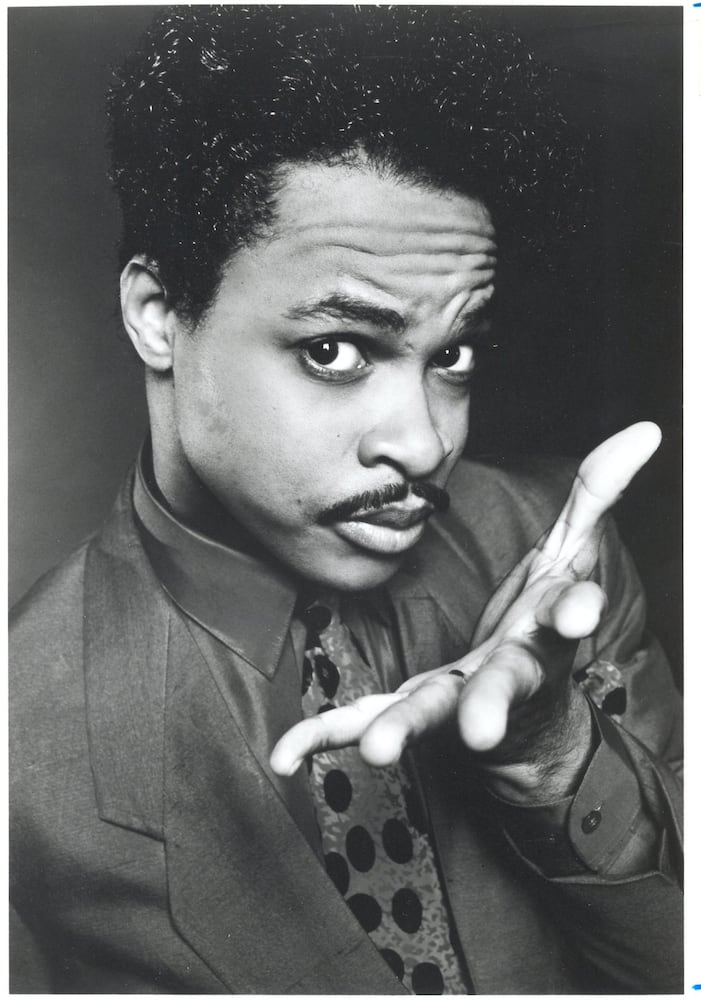

Credit: Contributed photo

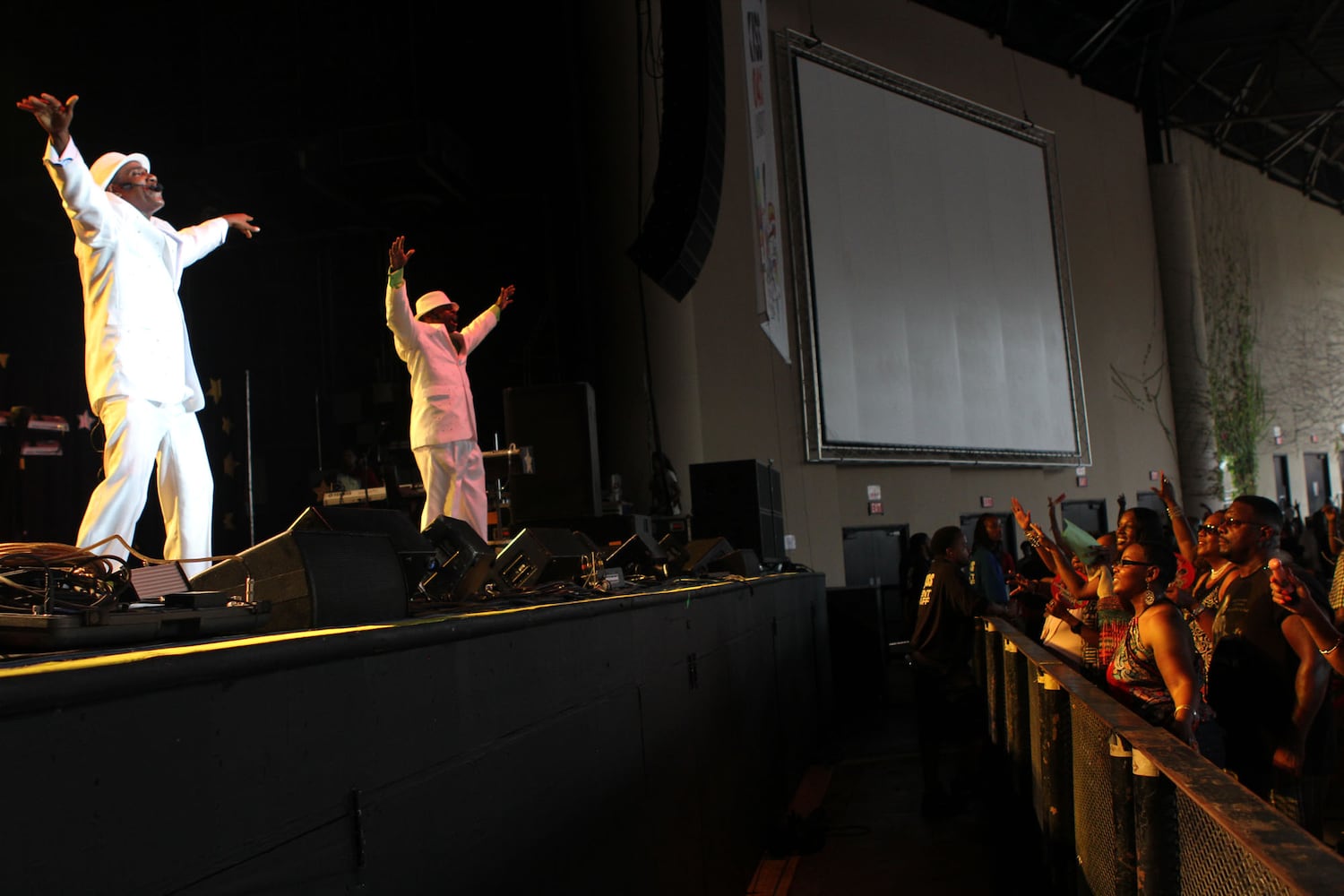

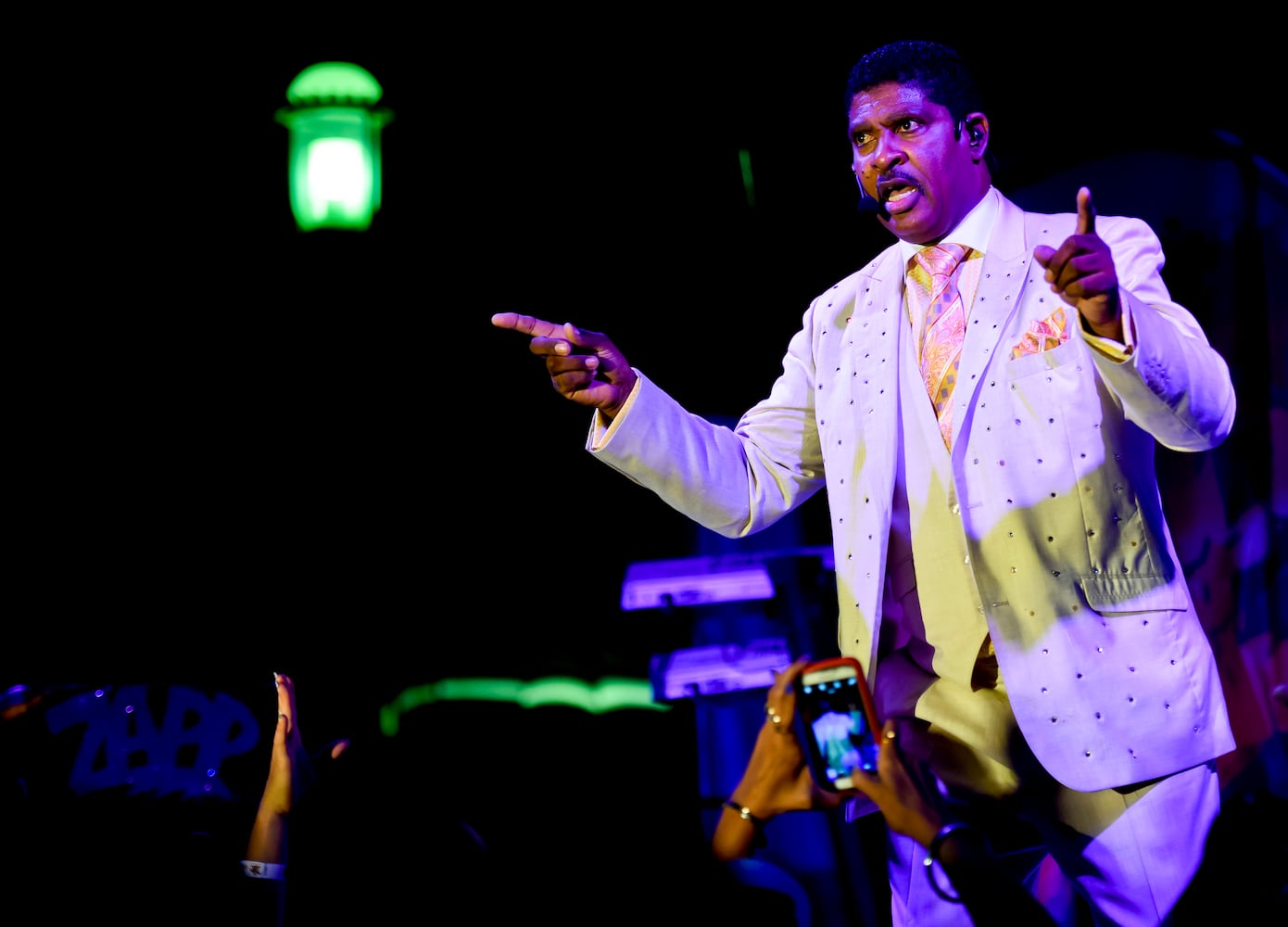

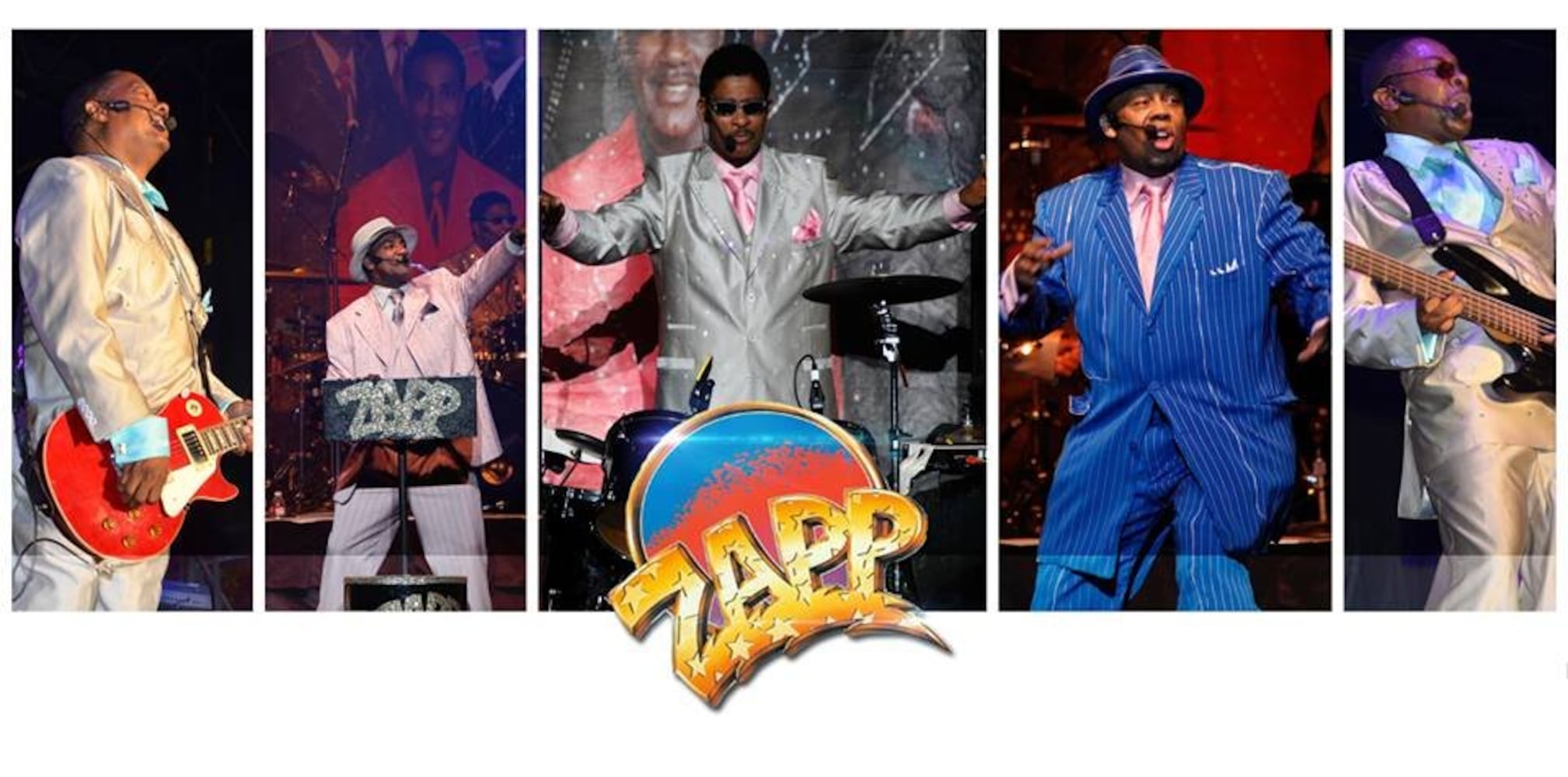

When Roger Troutman of Zapp mastered the “talk box” — actually a vocoder — he pushed the boundaries of the dancefloor party sound. Everyone was trying to sound futuristic, and Roger’s “talk box” involved placing a tube in his mouth, in which he would talk and sing into his keyboard and produce electrified human vocal sounds. The impact was exhilarating, creating hit after hit, and reached the Hip Hop world through his collaboration with Dr. Dre and Tupac on “California Love” in 1995. Zapp and Roger would become one of the most sampled acts in hip hop history.

Roger’s first national exposure came in 1976 on “Wanna Make Love (Come Flic My Bic)” by the Dayton band Sun, led by Byron Byrd, a band that indulged in interplanetary themes, over seven albums for Capitol Records from 1976 to 1982.

“It’s the Black experience. It’s the blues of the eighties. It has the same purpose with Black people as blues had for Black people when B.B. King started out, or Jimmy Reed.” Roger explained to me in 1995.

These Dayton artists were determined, and uniquely positioned to take the essence of the blues (the raw feel) and modernize it for the electronic generation, thinking far above and beyond, while still delivering More Bounce to the Ounce.

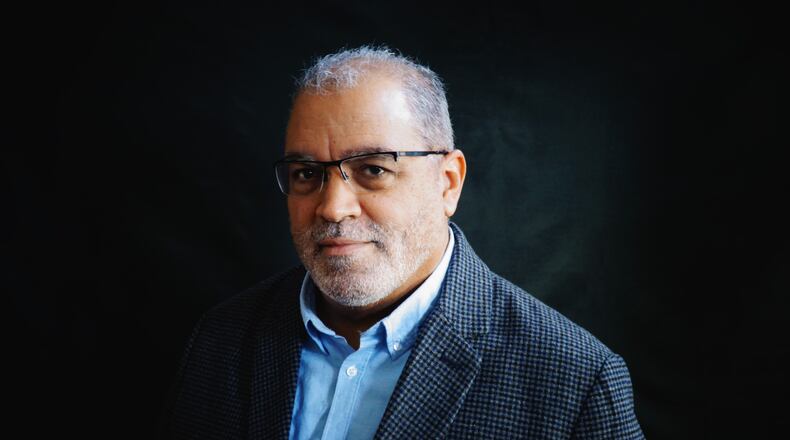

Rickey Vincent is the author of Funk: The Music, the People and the Rhythm of The One. (St. Martin’s Press 1996). He is Associate Professor of Critical Ethnic Studies at California College of the Arts, and is a lecturer at UC Berkeley. www.rickeyvincent.com.

Afrofuturism and Dayton, Ohio

Krista Franklin: "Transatlantic Turntable-ism." Collage on canvas. 2005.

"Afrofuturism demands society look beyond the present into worlds yet explored, where the fullness of Blackness blooms without limitation." - Read Russell Florence's story about Dayton's many connections to Afrofuturism. Throughout February, Ideas & Voices will feature artists and others to discuss our region’s contributions to Afrofuturism. You are invited to follow along.

|

Rickey Vincent: Dayton musicians did not engage in Black music traditions — they broke them |

|

Countess Winfrey: I challenge myself to create a new world, rather than shine light on the world we already live in |

|

Shon Curtis: Afrofuturism and the rebirth of artistic identity |

|

Leroy Bean: Valuing Black creativity: Addressing systemic bias in the arts |

|

Rodney Veal: ‘We are speaking loudly and with pride from our African roots’ |

|

Mariah Johnson: Libraries and artists in our community are the agents of change |

About the Author